For di side of one dirty road for Adré, one key crossing for di Sudan-Chad border, 38-year-old Buthaina sitdon for ground as oda women surround her. Each of dem get dia children by dia side. E no look like say any of dem get anytin.

Buthaina and her six children run from el-Fasher, one city wey dey under attack for di Darfur region of Sudan, more dan 480km (300 miles) away, wen food and drink no dey again.

“We no carry anythin wen we dey go, we just run for our lives,” Buthaina say. “We bin no wan go – my children bin dey top dia class for school and our life bin good for our house.”

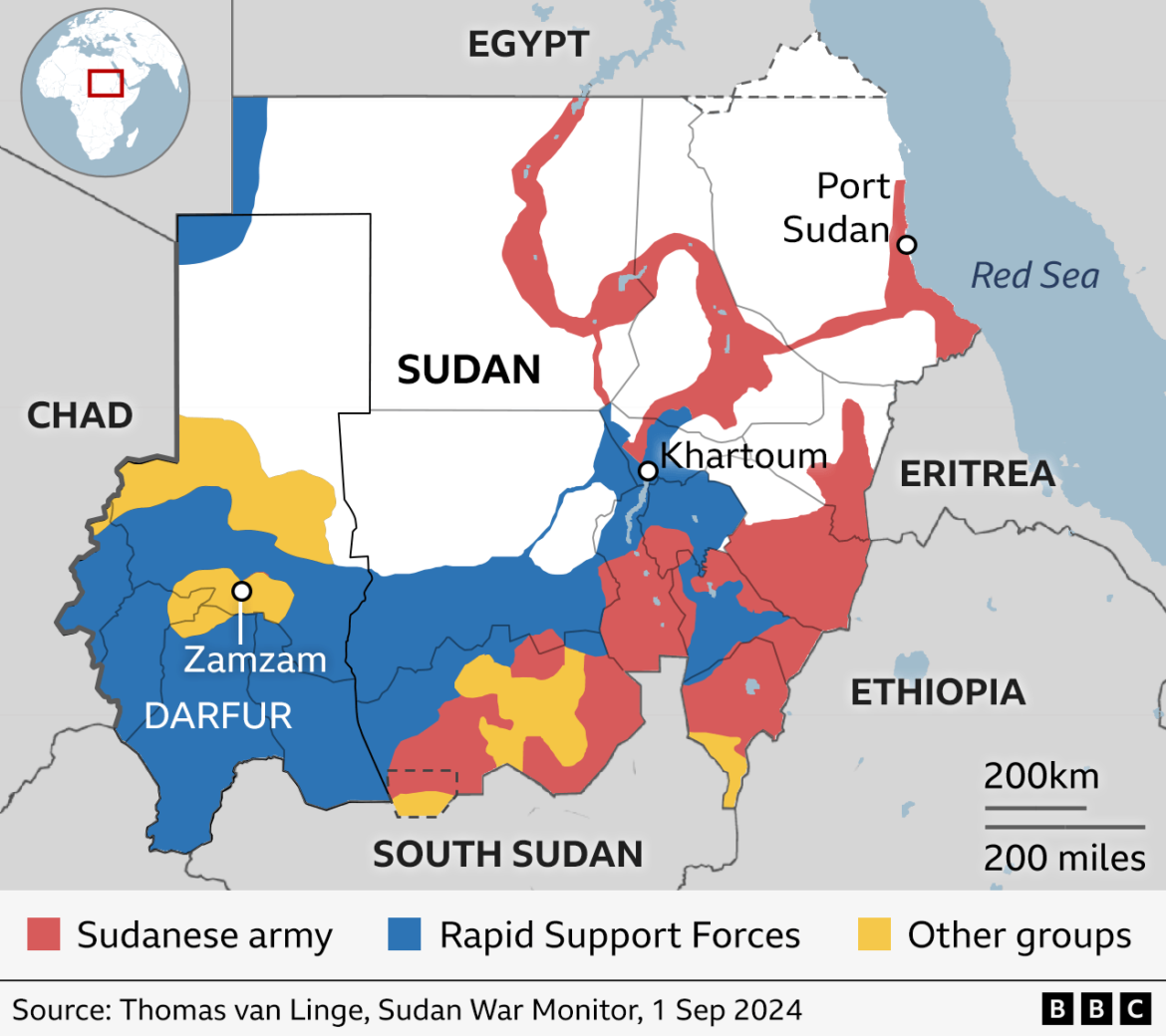

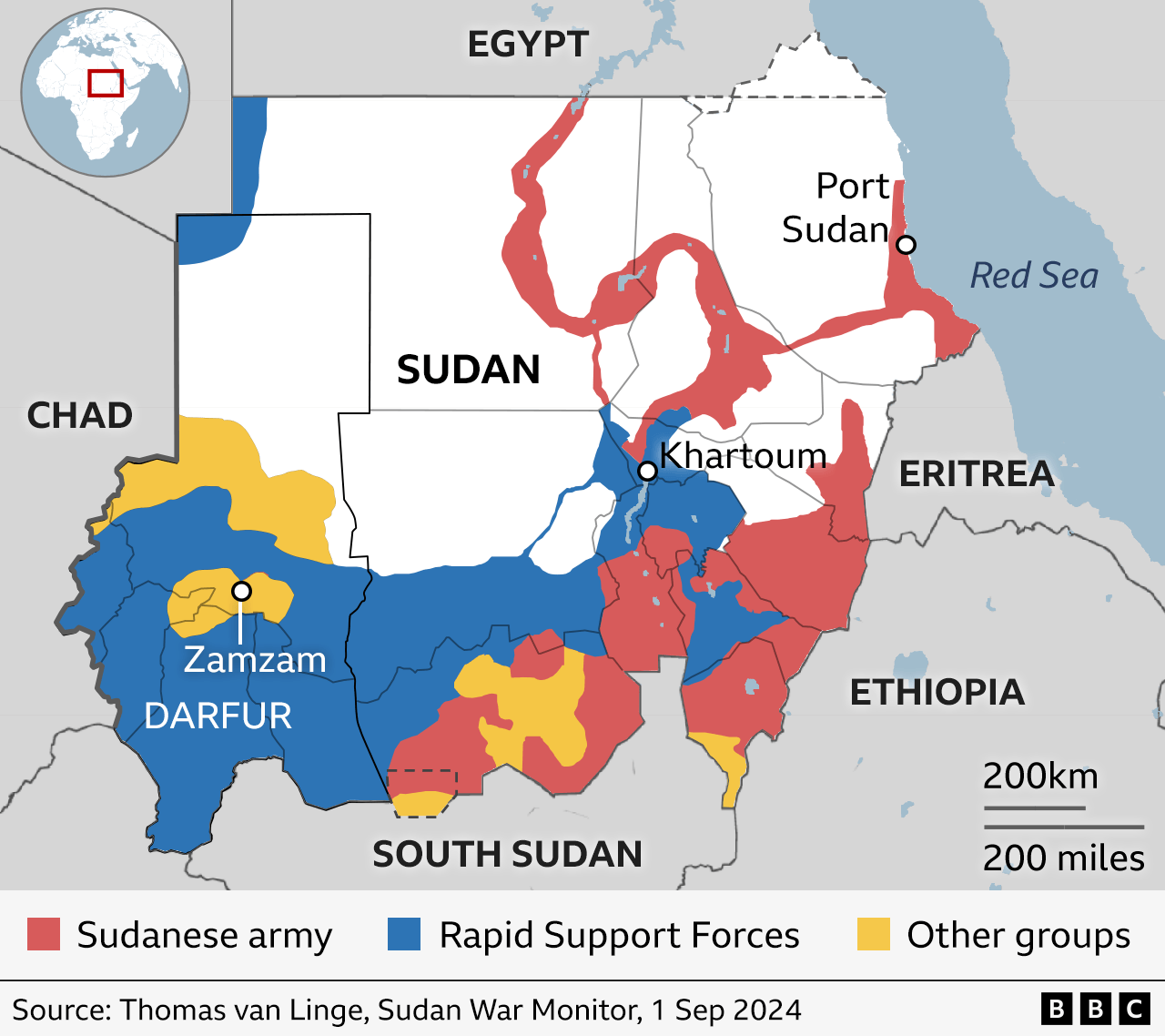

Sudan civil war begin for April last year wen di ruling army (SAF) and di rival Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary begin dia struggle for power, for different part ova di direction of di kontri.

Di war, wey show no signs of wen e go end, don claim thousands of lives, displace millions of pipo and throw parts of di kontri into hunger.

Aid agencies warn say Sudan fit soon experience di worst hunger for di world unless more serious help come.

Di BBC see di need of Sudanese pipo first-hand wen we bin visit camps for Adré, for di kontri western border, and Port Sudan, wey be di kontri main aid hub, 1,600km (1,000 miles) away for di east coast.

- Why fire service dey struggle to fight fires for Ghana, as dem record 50 fire incidents in one week

- Why Israelis dey protest against Netanyahu and wetin fit happun next?

- How more dan hundred inmates die for failed prison break

Adré na place wey now don become di symbol of di political failure and humanitarian disaster sake of di current conflict.

Until last month, di crossing bin dey closed since January, na only a few aid lorries wey dem allow into di kontri.

Dem don reopen am since but aid agencies dey fear say di deliveries wey dey come in, fit dey small or e dey come in too late.

Everi day, dozens of Sudanese refugees dey cross di border into Chad – many of dem na women wey dey carry dia hungry and thirsty children for dia backs.

Di moment dey arrive, dey go rush go di water tank wey di World Food Programme (WFP) set up, one of many UN agencies don dey try to raise di alarm ova di scale of di conflict humanitarian impact.

Afta we reach Adré, we make our way to one small camp, close to di border, wey di refugees bin make, wit wood, cloth and plastic wey dey use make di small camp house.

Rain start to fall.

As we comot, e come heavy and I ask weda di small camp house bin survive di heavy rain. “Dem no survive,” our guide Ying Hu wey be associate reporting officer from di UNHCR, anoda UN agency tok.

“Wit rainfall, a whole set of diseases dey come,” she add, “and di worst part na say e fit take days bifor we fit return hia wit car, becos of di flooding, and dat means say help no fit reach hia too.”

For one area dem declare serious lack of food – for Zamzam camp for Darfur – but dis na becos na one of di few places for war-torn Sudan wey UN get reliable information on.

Di WFP say e deliva more dan 200,000 tonnes of food between April 2023 and July 2024 – wey dey less dan wetin dem need – but both sides dey accused of blocking deliveries for di areas wey dey under rival control.

Di RSF and oda militant groups chop accuse of stealing and damaging deliveries, while di SAF chop accused of blocking deliveries into areas wey dey under RSF control, including most parts of Darfur.

Di BBC approach di RSF and di SAF about di accusations but dem no get any response. Both groups don previously deny say dem no dey stop di delivery of humanitarian relief.

One single convoy of aid trucks fit wait six weeks or more for Port Sudan bifor di SAF go clear am for onward travel.

On 15 August, di SAF agree to allow aid agencies to resume shipments through Adre, wey go provide di needed help to di population for Darfur.

For May, Human Rights Watch accuse RSF and Arab pipo say dem carry out ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity against ethnic Massalit and non-Arab communities for some part of Darfur.

Di RSF reject di accuse and say e no dey involved for wetin e call a “tribal conflict” for di region.

‘Everi day my pikin go ask, “Wia Baba dey?”’

During our tour of Port Sudan we visit one camp for pipo wey dey displaced within Sudan.

Walking from tent to tent, we hear one story afta anoda of loss and pain.

For one, group of women wey sit for circle, some hold dia babies tightly. All of dem share stories of abuse, rape and torture for RSF prisons.

One of di women, wey BBC no go mention name, say dem capture her wit her two-year-old son as she dey run comot from Omdurman, near di capital Khartoum.

“Everi day dem go take my son to one room down di hallway, and I go hear am cry as dem dey rape me,” she tell me.

“E happun evri time, so I go focus on im cry as dem dey rape me.”

Also for di camp I meet Safaa, mother of six wey run comot Omdurman too.

I ask her wia her husband dey, she say e stay behind becos di RSF target any man wey attempt to escape.

“Everi day my children ask me, ‘Wia Baba dey? Wen e go come?’ But I neva hear from am since January, wen we comot, and I no know if e still dey alive,” she say.

I aks about which future she see for her and her pikin, she say: “Which future? We no get future – nothing dey again. My pikin dey traumatised.

“Everi day, my 10-year-old son dey cry say e wan go home. We go from living for house, going to school and now we dey live for tent.”

Di BBC approach di RSF for comment about rapes and oda attacks but no response since. E don tok bifor say reports about say dia fighters dey responsible for widespread abuses na lie but wia some small number of incidents don occur, dia troops don dey accountable.

One Unicef employee wey show us around di camp say those wey arrive hia na di “lucky ones”.

“Dem manage to escape di fighting and come hia… dem get wia to stay and help dey,” im tok.

Crisis ‘fatigue’

Di BBC dey visit Adré and Port Sudan wit UN Deputy Secretary General Amina Mohamed and her team of UN executives, wey visit goment officials and Sudan de-facto president, Abdelfattah al-Burhan, to tell dem to keep di Adré crossing open.

Her aim na to put Sudan back on di agenda for di international community for time wen di world attention dey focused on conflicts for Ukraine and Gaza.

“E dey tiring becos e get so many different crises around di world, but dat no just dey good enough,” she say.

“You come hia and you meet dis mothers and dia pikin and you realise say no be just numbers.

“If di international community no step up, pipo go die.”